On June 16, 2016, The Atlantic printed an article by Ariel Sabar that leaves little doubt:

The fragment introduced in 2012 by Professor Karen King is a forgery.

The “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” Papyrus

Harvard Professor Karen King introduced the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” papyrus on September 18, 2012, in Rome at the International Congress of Coptic Studies.[1] After four years of debate and controversy, Professor King acknowledged in June 2016 that evidence gathered by Ariel Sabar of The Atlantic, “presses in the direction of forgery.”[2] The debate has apparently ended; Orthodoxy and skeptics can claim a win. Jesus was a bachelor!

But not so fast! The papyrus fragment in question is almost certainly a hoax perpetrated by a man in need of money who had the knowledge and skills to create a convincing forgery. He was able to persuade Professor King and other scholars and experts that the fragment was authentic. Unfortunately, this embarrassment makes it all the more difficult for independent researchers to get a fair hearing. The doors into the scholarly domain are now latched even tighter, and they were already all but locked to anyone lacking doctorate level credentials.

For the same four years the authenticity this fragment has been debated, we have been begging for one of these same scholars to test the evidence we’ve collected over the past fifteen years. The story of “Jesus and His Wife” can be found in scripture and in historians’ accounts of events in Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Rome. Granted, it requires scholars to consider the possibility that the ancient method of preserving history in enigmas has been successfully reconstructed and can be used to prove – or disprove – the historicity of Jesus. We have been called “amateurs,” and the method has been called “poor scholarship.” But no scholar, prominent or otherwise, has tested it as they tested this fraudulent fragment.

So, what are they afraid of? Robert M. Price may have captured the essence of their rejection of our work in his foreword to our book: “One dislikes to have to go back to the drawing board; thus one may uneasily wave away a case, a book, that would require that.”[3]

And, he’s right. It takes only a moment of reading to see that – if we’re right – everything they’ve studied, everything they’ve written, everything they’ve taught, is called into question. Why? Because they failed to take seriously some clearly-stated admonitions about the ancient method of writing “stories about the gods” and the associated method of interpreting the events described.

The most important admonitions come from the Greek historian Plutarch and the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria; both also offered clues to the method:

Plutarch: “… Whenever you hear the traditional tales which the Egyptians tell about the gods, their wanderings, dismemberments, and many experiences … you must not think that any of these tales actually happened in the manner in which they are related.”[4] In another essay he explains: “… whenever anything said by such authors sounds preposterous, and no solution is found close at hand, we must nullify its effect by something said by them elsewhere to the opposite effect…”[5]

Philo alludes to a similar method in the Hebrew language as he writes of the Essenes in “Every Good Man is Free”: “Then one takes up the holy volume and reads it, and another of the men of the greatest experience comes forward and explains what is not very intelligible, for a great many precepts are delivered in enigmatical modes of expression, and allegorically, as the old fashion was.”[6]

What Plutarch referred to “preposterous” Philo refers to as “striking statements.” Both were attempting to teach their readers how to identify and solve enigmas in order to get to the truth hidden within fables and myths. Furthermore, Plutarch demonstrated the use of this method in his version of “Life of Julius Caesar” (which appears to be an enhanced version of Nicolaus of Damascus’ earlier story). Both open with “preposterous” events typically expected for poems, fables, and myths. Plutarch then concludes his story with this “nullification”:

“These things may have happened of their own accord; the place, however, which was the scene of that struggle and murder, and in which the senate was then assembled, since it contained a statue of Pompey and had been dedicated by Pompey as an additional ornament to his theatre, made it wholly clear that it was the work of some heavenly power which was calling and guiding the action.”[7]

Pulling out the enigmatic clues (in italics), Plutarch reveals the secret: “These things may have happened … the place however … made it perfectly clear that it was the work of Ouranios Dynamis that was calling and guiding the action.” In other words, the man called “Julius Caesar” did not die; the assassination is a fable. Instead, Ouranios Dynamis produced and directed the events that have been accepted as “historical”; the man called “Julius Caesar” lived on even though the character “Julius Caesar” died. Ovid’s Metamorphoses explains that “deities” don’t die, they simply metamorphose; the man called “The Divine Julius” metamorphosed into another historical character – several other characters, in fact, but those identities are beyond the scope of this article.

In the fable of Jesus – told in the Four Gospels – both “Ouranios” and “Dynamis” make appearances: Mk 1:11: “And a voice came from Ouranos…”; Lk 1:35: “The messenger said to her, ‘The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and Dynamis the Most High will cast a shadow over you; Dio the child to be born will be holy; he will be called ‘Son of Theos.’”

Homer identifies “Dio” as “Zeus”(Latin, Jupiter).[8] Given this interpretation of Dio, this verse can be tied to the name given three verses earlier: “…you will name him ‘Ie-Sous’” (Lk 1.31" 1:31). However, Dio at Lk 1:35 is usually translated as “therefore,” sometimes as “so.” No wonder Church Father Irenaeus railed against using Homer to interpret scripture! “Name him YaH-Zeus” followed by “Zeus, the child to be born to you…” was indeed a heresy. But this is exactly the name that was transmitted in these two verses.

Several additional “coincidences” (or pieces of evidence) need to be added to determine the possibility/probability that Plutarch intended to reveal that a person or persons called “Ouranos” and “Dynamis” produced the fable that became the historical account of the mythological assassination of Julius Caesar.

The historical “Dynamis” who lived at the time of these events was Dynamis Philoromaios, Queen of the Bosporus Empire. Her grandfather was King Mithridates the Great Eupator Dionysius of Pontus,[9] and her uncle was Mithridates Chrestus.10] Ie-sous was not the first to be called “Chrestus.”

Archaeologists have discovered three statues that Queen Dynamis erected and dedicated to herself. Another was erected in honor of Augustus Caesar’s wife, the first Roman Empress, Livia Drusilla. In Phanagoria (a peninsula in the area of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov), Dynamis dedicated an inscription honoring Augustus as, “The emperor, Caesar, son of theos, the Theos Augustus , the overseer of every land and sea.”[11]

In another inscription at the same location Dynamis refers to herself as “Empress and friend to Rome.” In the temple of Aphrodite, Dynamis dedicated a statue of Livia, and the inscription refers to Livia as the “Empress and benefactress of Dynamis.”

Another coincidence: An early first century CE bust of Empress Livia was discovered at Arsinoe, Egypt, and Cleopatra’s younger sister was named “Arsinoe.” Arsinoe and “Livia” were about the same age;[12] Cleopatra and “Dynamis” were about the same age.

Queen Dynamis’ husband was Asander, a derivative of Alexander, surnamed “Philocaesar Philoromaios” (“lover of Caesar, lover of Rome”).[13] Like Julius Caesar, Asander was born c. 109 BCE, but he outlived Julius by twenty-seven years. Asander died in 17 BCE, the year Augustus (“Son of Theos,” according to Dynamis) reinstated the Secular Games, the same year that money maker M. Sanquinius fashioned coins that depict a comet over the head of a wreathed man, assumed to be Julius Caesar. This conclusion is drawn from Suetonius, who reports that shortly after Julius was assassinated in 44 BCE, and just as the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris was getting underway, “a comet shone for seven successive days, rising about the eleventh hour, and was believed to be the soul of Caesar.”[14] Construction on the larger of the two Pyramids in Rome (the one destroyed) was also started at about this time.

Julius initiated the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris in 46 BCE to dedicate his Temple of Venus and to affirm that he was descended from Venus through Iulus, the son of Aeneas. In Aeneid, written between 29 and 19 BCE, Vergil honors the deified Julius with this catchy little phrase: “Go forth with new value, boy: thus is the path to the stars; A son of gods that will have gods as sons.”[15] Vergil is referring to the offspring of Julius Caesar, who was, indeed, deified: “After his death a statue of Julius Caesar was placed in the temple of Quirinus with the inscription ‘To the Invincible God.’ Quirinus, to the Roman people, was the deified likeness of the city's founder and first King, Romulus.”[16]

Asander and Dynamis had one known son, Tiberius Julius Aspurgus Philoromaios.[17] He was born about the same time as “Caesarion” and “Emperor Tiberius Julius Caesar.” His wife, known only through numismatic evidence, was Gepae-pyris.[18]

Tiberius and Gepaepyris had two sons; the eldest was “Tiberius Julius Mithridates Philo-Germanicus Philopatris” (“son of Mithra, lover of Germanicus, lover of father”).[19] Their second son was “Tiberius Julius Cotys I Philocaesar Philoromaios Eusebes” (“lover of Caesar, lover of Rome who is the Pious One”).[20] Two sons: “Lover of father Germanicus” and “Lover of Caesar, Lover of Rome, The Pious One.” They were about the same age as Emperor Tiberius’ only known biological son, Drusus, and the name “Germanicus” associates this son of Tiberius Julius Aspurgus with Emperor Tiberius Julius Caesar’s adopted son and heir, Germanicus.

When Asander died, so the story goes, a man by the name of “Scribonius” pretended to be a relative of the widow Dynamis and forced her to marry him, making her a “Scribonia.” And Augustus Caesar’s second wife – mother of Julia the Elder – was also named “Scribonia.” In fact, Scribonia was the grandmother of Agrippina the Elder and Julia the Younger. These sisters gave birth to sons at the time of the first census of Quirinius, 6 CE. These two boys are known to historians as “Paulus the Younger” and “Germanicus the Younger”; notably, their fathers – also named “Paulus” and “Germanicus” – were born “when Herod was King.” Their counterparts in the New Testament, of course, are “Elizabeth,” her relative “The Virgin Mary,” and their sons, cousins “John the Baptist” and “Jesus the Nazarean.”

Furthermore, the author of Acts of the Apostles ties “Jesus” to “Aeneas,” and therefore to Julius Caesar: “…Aeneas Jesus Christ heals you;[21] get up and make your bed! And immediately he got up” (Acts 9:34).[22]

Often noted but generally ignored is the important fact that “The Caesars, beginning with Augustus Caesar, were called ‘Theos.’”[23] The “Divine Julius Caesar” died on March 15, 44 BCE; Emperor Tiberius Julius Caesar (aka, “Theos”) died on March 16, 37 CE. March 15 was The Ides of March, the first day of a week-long celebration of the myth of the Roman deities Cybele and Attis. According to the myth, Attis died beneath a pine tree and violets sprouted from the drops of his blood. The climax of the Ides of March celebration was to chop down a pine tree, cover it with violets, and carry it in a procession to the shrine of Cybele, the Magna Mater. On the third day after his death, Cybele would bring Attis back to life and a joyful celebration would commence.[24]

“Attis” is also written “Atys”; the Hebrew word for "tree" is pronounced exactly the same as Attis: ets (Strong’s No. 6086), which notes, “phonetic spelling: ates” (pronounced Attis). Furthermore, ets (pronounced Attis) is sometimes translated as “carpenter.”[25] Now look at what happens when the Hebrew word for “carpenter” is inserted into Mk 6:3: “Is this not Etys (pronounced “Attis”), the son of Mary…” The Hebrew Sefer - from which The Gospel According to Mark was most likely taken - identified "YH-Zeus" as the Hebrew version of the Roman's "Attis." Another enigma is solved.

Like “Attis” before him, Mark’s “Etys” was resurrected on the third day after his death. Scholars have long debated why the earliest version of The Gospel According to Mark ends abruptly at 16:8. At least two ancient scribes attempted to add endings that satisfied the orthodox patriarchal version of the story of Jesus.[26] Considering the many parallels between the myth of Attis and the story of “Jesus the Etys,” it seems likely that “The Magdalene, Mary”[27] like “Magna Mater, Cybele,” might have played some role in the original, "unorthodox version" of the resurrection. This version, of course, was the hated and denigrated "Nazorean Heresy." However, it is one of the secrets Jesus the Nazorean shared with his closest disciples.

Now, let’s pull on a few more threads and see what additional enigmas can be unraveled: Josephus writes: ”So Pilate, when he had waited ten years in Judea, hurried to Rome, and this in obedience to the orders of Vitellius, which he dared not contradict; but before he could get to Rome, Tiberius was dead.28] But Vitellius came into Judea, and went up to Jerusalem; it was at the time of that festival which is called the Passover.[29]

Josephus’ chronology dates these events to the Passover of 36, the year Pontius Pilate was removed as prefect. Curiously – and notably – Pilate left Jerusalem with orders to return to Rome, and in spite of Josephus reporting that he “hurried to Rome,” he didn’t arrive there until after Tiberius died – March 16, 37, during the Ides of March celebration. From Jerusalem to Rome by water during the summer months – depending on the weather – took between fifteen and thirty days – not a year. Therefore, Pilate either didn’t “hurry” or he didn’t leave for Rome until a year later.

And so we are left with a question: Where was Pilate between Passover of 36 when he was ordered to return to Rome and Passover of 37? We know he wasn’t in Rome because he arrived there some unspecified time after Caligula became Emperor on March 16.

When “Theos Tiberius Julius Caesar” allegedly died during the Ides of March in 37, the rumor spread that Caligula poisoned him and ordered that his ring be taken from him while he still breathed. “…and then suspecting that he was trying to hold fast to it, that a pillow be put over his face; or even strangled the old man with his own hand, immediately ordering the crucifixion of a freedman who cried out at the awful deed.”[30]

This scene is dated to March 16, 37 CE. The next Jewish Passover would follow a month later – April 19, 37 CE. From Capri to Jerusalem took less than a month; therefore, this enigmatic “freedman who cried out” could have been transported to Jerusalem in time for the “Annual Passover-Passion Festival” and a notable “Crucifixion.” One "freedman" stands out because of his immense influence on Emperor Claudius, and because of his name: "Narcissus." The poet Ovid writes of Narcissus: "When looking for his corpse they only found, a rising stalk with yellow blossoms crowned." This is the myth of the Easter Lily, which legend says sprang up from the ground where drops of Jesus' blood fell. (http://www.dgreetings.com/easter/easter-lily-history.html). Paul, at Romans 16:11, also greets someone called "Narcissus."

As impossible as it might seem, evidence suggests that ancient historians preserved the history in enigmas. And the history of Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, and their descendants – the one shrouded in Plutarch’s enigmas – is intertwined with the Story of Jesus and Mary Magdalene – the one shrouded in enigmas that are scattered about in the New Testament.

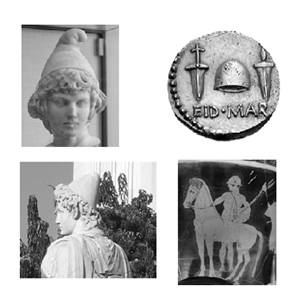

Top left: Attis as a child in Phrygian cap, 2nd century ACE.[31]

Top right: Denarius featuring a pileus, issued by Brutus c. 44 BCE. The handle of one sword appears to be a cross, the other seems to suggest a flame.[32]

Bottom left: Dioscure in pileus, 4th Century CE. Rome, Italy, Piazza del Campidoglio.[33]

Bottom right: Dioscure in pileus, c. 460-450 BCE. Paris, France, Louvre Museum.

[1] Professor King’s introduction of the fragment: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gospel_of_Jesus%27_Wife.

[2] Online article: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/06/karen-king-responds-to-the-unbelievable-tale-of-jesus-wife/487484/.

See original Article: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/07/the-unbelievable-tale-of-jesus-wife/485573/.

[3] Robert M. Price, Author of The Incredible Shrinking Son of Man, The Amazing Colossal Apostle, and

The Pre-Nicene New Testament, Foreward to Following Philo: In Search of The Magdalene, The Virgin, The Men Called Jesus, by P.J. Gott and Logan Licht.

[4] Plutarch. Isis and Osiris XE "Ancient Texts:Plutarch, Isis and Osiris" , “Introduction,” (Loeb Classical Library, 1914, Babbit trans.), n.p. [cited 22 May 2009], Bill Thayer’s Website. Online: <http://www.penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/ Moralia/Isis_and_Osiris*/A.html.> Emphasis added.

[5] Plutarch, “How the Young Should Study Poetry,” http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0141%3Asection%3D4 (after footnote 20), 106.

[6] Yonge XE "Yonge, C.D." (2013): Philo, “Every Good Man is Free (12.82), 690. Emphasis added.

[7] Plutarch, Life of Julius Caesar (Loeb, 1919), (Thayer Online XE "Plutarch" XE "Ancient Texts:Plutarch, Life of Julius Caesar" 66.1).

[8] Middle Liddell.

[9] Adrienne Mayor, The Poison King: the life and legend of Mithridates, Rome’s deadliest enemy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 364.

[10] Mayor, 2009, 45.

[11] S.T. Davis, D. Kendall, G. O'Collins. The Trinity. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 30. (N.V.)

[12] https://quizlet.com/22939129/art-history-the-roman-empire-republic-through-late-empire-7-flash-cards/

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asander.

[14] Suetonius XE "Suetonius" , Life of Julius Caesar XE "Ancient Texts:Suetonius, Divus Julius, 88." (Loeb, 1914), ( Thayer Online 88.1).

[15] Virgil, Aeneid (New York: Penguin Books, 2006), 287. Book IX, line 641, spoken by Apollo XE "Apollo" to Aeneas’ young son Iulus.

[16] Cassius Dio XE "Cassius Dio" , Roman History (Loeb Classical Library 1916), 292-3. Bill Thayer’s Website, Online Version, 43.45.3. <http://penelope.uchicago.edu /Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/43*.html> XE "Ancient Texts:Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities"

[17] Ellis Hovell Minns, Scythians and Greeks: A Survey of Ancient History and Archaeology on the North Coast of the Euxine from the Danube to the Caucasus. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 590-6. This book supports with archaeological and numismatic evidence the summarizing Wikipedia article, “Tiberius Julius Aspurgus.”

[18] Minns, 1913, 594-596 , in support of Wikipedia, “Gepaepyris.”

[19] Minns, 1913, 598, in support of Wikipedia, “Tiberius Julius Mithridates.”

[20] Minns, 1913, 598, in support of Wikipedia, “Tiberius Julius Cotys.”

[21] Philo’s rules, no. 16: the artificial interpretation of a single expression; no 5: an entirely different meaning may be found by… disregarding the ordinarily accepted division of the sentence in question into phrases and clauses.

[22] Emphasis added.

[23] Philip W. Comfort XE "Comfort, Philip W." and Eugene E. Carpenter XE "Carpenter, Eugene E." . Holman Treasury of Key Bible Words: 200 Greek and 200 Hebrew Words Defined and Explained; 290.

[24] N.S. Gill, “Cybele and Attis - The Love Story of Cybele and Attis:

The Phrygian great mother goddess Cybele and her tragic love for Attis.” http://ancienthistory.about.com/cs/nemythology/a/cybeleattis.htm

[25] Strong’s Hebrew No. 6086.

[26] For a detailed explanation of the interpolated endings, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_16.

[27] Migdal is a Hebrew word that means “Watchtower.”

[28] Josephus XE "Josephus" , 1999, Antiquities XE "Ancient Texts:Josephus, Antiquities" 18.4.2 (89), 593. (Tiberius died March 16, 37 CE.)

[29] Josephus XE "Josephus" , 1999, Antiquities XE "Ancient Texts:Josephus, Antiquities" 18.4.3 (90), 593.

[30] Suetonius XE "Suetonius" , Life of Caligula XE "Ancient Texts:Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Caligula" (Loeb, 1914), (Thayer Online 12.2-3).

[31] Currently at Cabinet des Medailles. Photograph by Jastrow, 2006

[32] Image from Wikimedia Commons; no source cited.

[33] Photograph: Carlomorino public domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Return to The Nazarene Way main menu